Look And Look Again

Maciej Urbanek in conversation about his landscape series

By Ania Ostrowska

I find myself at Maciej Urbanek’s studio, within Tileyards Studios, King’s Cross London. I am strategically seated by the artist to see both him and his works on the walls and the floor behind him: Maciej himself seems part of a landscape of his own making. I am familiar with the entire body of his work but this interview has been inspired by and is mainly concerned with four series of Maciej’s landscape prints: Goldleaf, Volatile Matters, Lyre Lyre and The House of The Serpent.

Looking at the works from your landscapes series, I catch myself thinking: ‘Of course I know what that is,’ only to question my initial certainty as soon as I take a second look. Is that a reaction you’re happy with/ trying to elicit?

I am very happy with this reaction! This is probably the first time that somebody described their impression of the works in such a way although this is something in which, in a serious and profound way, I am interested. My work is based in photography and photography has this uneasy relation to reality, it is recognisable essentially, you photograph things in the world and they become things that you can afterwards name. In case of my work you can recognise they are forest, plants or foliage and sometimes animals, you recognise there’s a water element.

How important is it then to establish what they are?

My understanding of photography and the core of my interest in this medium is it’s relation to reality- with representing reality or “presenting” reality: I am not sure which would be more suitable word in this context. I think the process of recognising is inherent in photography. In that sense I acknowledge, yes, you recognise what you’re looking at but it’s almost the second part that is important to me and what I am trying to do in my work: that you question what you are looking at. At this moment the process of looking is freed from patterns of recognising, classifying and compartmentalizing certain things, it is more an active process of trying to have a second look or a more detailed look or trying to decipher what you’re looking at in a way that is less prescribed or freed from set ways or constraints of a “normal” look.

You are talking about uneasy relation between photography and reality. I’d like to take a half step back: especially in case of landscape series, there is also a relation between photography and the concrete place: I know these pictures were taken in Australia and North America. Does it matter?

It’s an interesting question because on a sort of dogmatic level I think it’s unimportant to name the places. The titles of the series don’t include the names of the places or the hints to where those places are, they are more poetic and literary titles in that sense. Because of my approach to the link between photography and reality, I do not treat photographs as documents in any sense. I don’t treat them as traces… well, “traces” is a different word and maybe too complicated but I don’ treat them as testimonies of places, as…

“It’s about energies, impressions and feelings that the place is providing me with; I get things from the place rather than I take the place as it is”

Records?

Yes, “records” is probably the best word to use. I don’t treat them as ‘Here I was’ statements. So to me photography is not a window that’s looking into a place that was recorded somewhere else. Photography to me is more of an illustration, like traditionally understood medium of painting or drawing and in that sense it is almost like writing… But let me just add something: I said it’s problematic and that on the dogmatic level I don’t link them but at the same time, whenever I’m showing the works to people I do say: it was Florida, it was Arizona, it was Alaska, it was a desert in Australia and that makes me question again what this relation between the place and the instance of taking a photograph in that place and the product of this process is. Maybe it is more like with poems, that poet goes somewhere and the place inspires him or her to write a poem but it’s not really like naming the place in the poem, it’ s more about energies, impressions and feelings that the place is providing them with. I get things from the place rather than I take the place as it is.

We have talked about it before: your photographs look like paintings to me, both in their texture and composition…

Let me just interrupt: I think you should be saying ‘your prints’ not ‘your photographs’. It’s an important distinction.

Of course, I will. You have just mentioned poetry but I would like to ask about the link between photography and painting. How is this blurring of the boundary between the two desired/useful for you? Put bluntly, why do you want your prints to look like paintings?

I don’t know if I ‘want’ them to look like paintings or whether they just end up looking like ones. It is intentional but my point of departure isn’t: ‘I’m going to make a print that looks like a painting’. That’s why I interrupted you with the “photograph” versus “print” distinction. I find a ‘print’ refers to the object, the thing you’re faced with as a viewer whereas ‘photography’ in my mind and in my practice refers to the process or technique of using the device that uses light and uses lenses and uses form of recording to arrive at something.

However, I meant “a photograph” rather than “photography”…

I think there isn’t anything like “a photograph”. The prints of photographs, yes. I think this is important to answer your question about photography and painting as it is going back again to reality, it is about looking at something and recognising something. When you look at my prints, they have the presence that you recognise only when you’re faced with them in the flesh. They’re quite large and very detailed and when they are reproduced online or printed in some publication or a newspaper, they’re different but in the flesh they are occupying quite a lot of your view space.

“My works look like drawings or etchings or paintings and they bring it back to quite a subjective process, a subjective rendering of reality just like paintings or drawings are and not objective like photography is being thought of”

Size does matter.

Well, in this case yes because of the material quality of them: you look at the surface of the paper that is porous and fuzzy, you look at the inks and how they… what’s the word… fade one into another. They look like drawings or etchings or paintings and in that sense they bring it back to quite a subjective process, a subjective rendering of reality just like paintings or drawings are and not objective like photography is being thought of. So I am referencing the languages within fine art that have everything to do with me being a creator rather that some sort of objective person who takes a photograph of something. I do understand photographs like that, the great photographers of landscapes like Ansel Adams: I see those works as masterpieces of composition, of referencing drawing or painting, ink painting etc. In that sense I’m going back to the language that very often concerns painting like “composition”, “light”, “colour”. As far as the medium is concerned it’s almost like the build-up of lies or mimicries or things pretending to be something else. And I like the fact that within that you can just enjoy the materiality of the print, you can enjoy the intensity of a certain colour, you can enjoy a certain line, a certain detail within them on this painterly level or the drawing level rather than photographic.

My next question is precisely about detail. Least in the Volatile Matters series, which is almost monochromatic, in other ones the use of colour seems deliberate and crucial. Could you talk a bit about that?

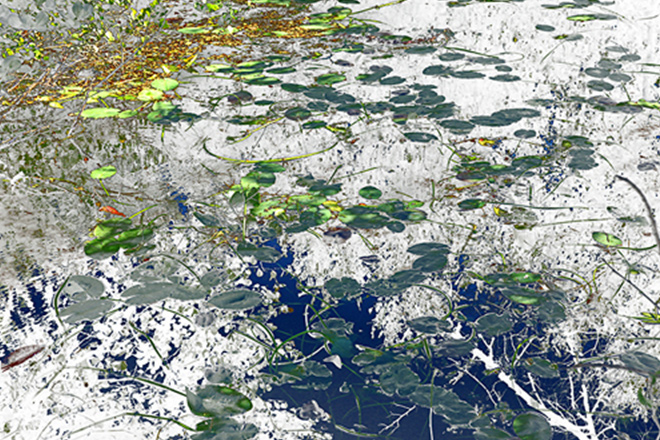

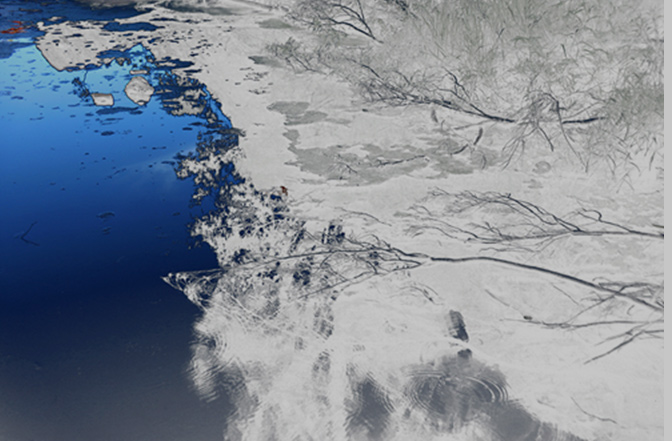

The first work from The House of the Serpent series, the most recent series I’ve done, this work is all about blue. It’s a work that pictures the side of the small lake at the bottom of the gorge and you can see the foliage, that looks like it’s drawn, on the right hand side. Almost half of the work on the left hand side is occupied by this gradient of blue that comes almost all the way from deep grey, through deep marine blue, with the shades getting brighter and brighter ending up at the top of the picture with neon electric blue almost. It’s almost like a fetish to me to be looking at this blue.

“In these large works, meter-and-the-half by meter, you have just tiny dots of violet: it gives me goosebumps every time I look at them and see them there because they’re so crucial in that sense”

Similarly in some of the works from the Goldleaf series there are some blades of grass that are very bright yellowish neon green, they cut through the work. You mentioned the Volatile Matters series and I agree this is the most monochromatic series but even there, in the far more nuanced way, in some works you can see little splashes of deep violet, of the flowers that were there in Alaska in the background. So in these large works, meter-and-the-half by meter, you have just tiny peppered dots of violet: it gives me goosebumps every time I look at them and see them there because they’re so crucial in that sense. You asked how ‘deliberate’ it was and I am not sure it was deliberate. It’s more it was there for me to take, I just point: ‘Look…’

Like a spotlight?

In a sense. The works were executed in different parts of the world and what is fascinating for me as an artist is noticing how much the green differs. They’re nature so obviously you’re going to have plants and the green but they’re from different parts of the world, illuminated with a different light, they create completely different feelings and emotions, starting with these electric neon yellowish greens from Florida and ending on these almost khaki, dark rotting greens of grim and murky Alaska.

This brings us back to the issue of connection with the place, this time on the level of technique…

Obviously, I wouldn’t be able to make these works if I didn’t travel to all these different places.

“I want to preserve the complexity that is in front of me but I also want to draw the attention to every single particular thing that is there. I want to be able to identify every single leaf and flower and blade of grass and every single nuance and detail of what I’m looking at”

Bar one crocodile I have spotted in the Goldleaf series, the pictures are quite uninhabited. Why is that?

Actually it’s an alligator (laughs). Well, there’s a bird as well… in couple of the works from this series there are small animals. But yes, not too many and there is quite a practical reason for that: it is actually hard to photograph animals in the wild and I am not a wild life photographer. I guess the good answer to this question is that I am predominantly interested in forest and jungle as complex systems. Obviously, animals are part of it and an inherent part of it but they’re often hidden and they’re there, you just don’t see them. Sometimes you see paths, in the Volatile Matters series you see the paths in the foliage that animals used, moose or elk I guess (laughs). But that’s not really important because what I’m interested in is these really intense, complex systems that I call “forest” or “jungle”. It’s like in the saying “you cannot see the forest for the trees”. When you look at the jungle it’s almost like an impenetrable thing, it’s a whole, a thing, an entity of its own, and with the way I treat my images and how I process them, I want to dissect it. I want to preserve the complexity that is in front of me but I also want to draw the attention to every single particular thing that is there. I want to be able to identify every single leaf and flower and blade of grass and every single nuance and detail of what I’m looking at. It’s almost like an accidental, busy universe that is holding itself by a thread. But it holds itself: it’s all there in front of you.

It’s a very compelling answer but what about people? You are not a wild life photographer, but you are there, a human being, with your equipment taking photos. Are you trying to preserve the landscape as unspoilt, devoid of people?

No, not really. I have series of figurative works and human figure is very present and strong and interesting subject for me. But not in these four nature series, and it’s not for a particular reason that I’m deciding there’s not going to be people there… People don’t really belong there, in a sense. It would be hard for me to push somebody into a bayou or a swamp n Florida to be there with the alligator, it would be obviously staged. I’m interested in “figures” more than people; I’m interested in bodies rather than personalities. In my figurative works, the works that take “figure” as their main subject, you’re not going to see faces, there are very few faces but I’m not interested in that because I’m interested in definitions in a way. I’m not saying the faces won’t appear in the future but in the landscape series, a person would become an axis of the picture, they would become a focal point of it as people are, whereas in these works it’s all about the complexity of the jungle or the forest.

“A friend of mine told me recently that looking at my works made him feel ‘cool’ in a sense of being refreshed: ‘Your eyes are really wide open and you notice everything, feeling you have space for everything, this refreshing coolness’”

Nature as shown in your works is strikingly beautiful. Are you interested in the dimension beyond the beautiful, beyond the aesthetic level, which by way of a shortcut I would call “the sublime”? Of course, every viewer’s response will be different, but where would you like to send you ideal viewer’s thoughts?

The relationship between the beautiful and the sublime is one that has been analysed and talked about for centuries and is very complex…

I would like it here to signify just the dimension beyond aesthetic beauty.

I don’t think that’s how it would be understood though. “The sublime” in this most common understanding is something that is so overwhelming that it makes you as a person feel small and inferior, there is some sort of trembling or fear connected to the sublime… I am very cautious about using these sorts of terms. At first, when you started to ask this question, you said my works were beautiful and you used “beautiful” in quite a colloquial sense which I really liked because it didn’t refer to the distinction between beauty and sublime, you just said they were beautiful, that on the aesthetic level there is something that gives you pleasure.

All right then, let’s forget the sublime. What I am asking about is the “beyond” beautiful, whatever this may be or whatever we call it.

One of very strong references in my art practice that directly connects to these series of landscapes and indirectly to all the others is the poem from the 1933 by Polish poet Julian Tuwim called ‘Trawa’ (Grass). In the work the poet is addressing the grass that’s up to his knees, we’re assuming he’s standing in the meadow or similar, demanding of the grass to grow all the way up to his forehead. He says he wants the grass to grow all the way up to his forehead so he wouldn’t be able to distinguish himself from the grass so it wouldn’t make any difference whether either would be called “grass” or “Tuwim” (his last name). This is the state of forgetting or being lost, I don’t really like the phrase of ‘being transported somewhere’, I am not transporting people anywhere…

“In all landscapes series there are these spaces in-between, the spaces you can inhabit, the spaces you can navigate through within the landscape, within the work, and get lost”

Would you rather like your audience to melt in your landscape, to lose their subjectivity, to be selfless?

“Subjectivity” is heavy-duty terminology again (laughs). I love “selflessness”! In the works when you look at them there’s quite a lot of white and it once again references drawing on white paper. Especially in Victorian typology drawings you have this work on the uniformly white background, this detailed, very detailed drawing of a plant or something. And those white spaces to me are crucial because they have something to do with the process of abstraction. In all these series they are the spaces in-between, the spaces you can inhabit, the spaces you can navigate through within the landscape, within the work, and get lost. You can be almost on the same axiological or a value level as a blade of grass or a fern or a flower or water, you can be part of it, you can get lost, you can get emptied. In this sense “becoming one with” is at the very centre of my interest.

I’ve had a visitor recently, a friend of mine from the Royal Academy, and he said looking at the works they make him feel ‘cool’ in a sense of being refreshed: ‘Your eyes are really wide open and you notice everything, feeling you have space for everything, this refreshing coolness.’ I like that, this reaction to the work. Beauty is very important and I feel beauty is a word that in contemporary culture and life has been trivialized. It’s almost unfashionable to talk about beauty, it refers to some culture in celebrity world that is supposed to be referencing female and male body and the face and the youth and there are so many other attitudes towards beauty. I think this is a very potent concept that deserves attention and deserves to be used in a serious, profound, valuable way.

The answer you just gave me about your audience melting into a landscape points more towards holistic, so-called ‘Eastern’ spirituality, the ideas about becoming one with nature. A standard Christian reading of your work would probably be: ‘It’s so beautiful, we shall think about the hand of the Creator behind all this beauty’. How do you feel about that?

I am very interested in theology and discourses on religion and I have researched a lot and written a lot about it, it’s present in my work, everyday thinking, attitudes and everything that has to do with it. But I don’t want to limit my artistic enquiry to the notions of God and religion. I can comment on it as it’s very important for me. What I am trying to achieve and what I would like the work to do is room for…. going back to your first question… it’s about questioning again and looking back. And this ‘questioning again’ I understand as the contemplative nature of the works, I would hope that they give you room and that they enable you to contemplate. The word ‘contemplate’ has a religious tint as well, you think about the monks, you think about priests contemplating God etc. But I want to think about it broader. So as to the distinction between ‘Eastern’ religions and Christianity, they may not be so far apart. A friend of mine is writing an article about the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins and my work. Hopkins was a Jesuit priest and he was writing about the concept of ‘inscape’, which very much has this ‘Eastern’ meaning of something immersive, something that you get lost within. I am not sure to what extent ‘the hand of the creator’ is there in my works. If people looking at my works think about God, it’s fine, if they think about beauty it’s fine too, about overwhelming complexity of nature and the universe, all these things are subjects of my work and I have to be responsible for all these references that I myself put in there and people draw from the works. The spiritual/religious narrative of the works, I find it fascinating… I wanted to do a project in the Vatican Gardens once. There is a certain part of Vatican Gardens called ‘The Casino’, where the pope goes not to think about God. As the head of the Roman Catholic Church, the pope is occupied with God all the time, conducting masses etc.

So what does the pope think about when he doesn’t think about God?

That’s the question I find fascinating! My tutor at the Royal Academy of Arts Vanessa Jackson told me about it but I haven’t verified it… Anyway, I am attracted by the concept: a place within the Vatican Gardens, there is probably a bench or something and the pope can go there and relax and not think about God, being surrounded by nature. Another thing I find fascinating, drawing on and broadening the understanding of the plants and the jungle and the forest and calling it “the Garden”… In regression therapy when they take you back and back through your incarnations, the place you arrive at is actually the garden.

…of Eden?

That’s questionable because it’s so Christian. But regression therapists take you back to your own garden, they go back through incarnations and then you’re just left in the garden. I find it amazing that in the symbolic order human decided that where we come from, the starting point, or the most private place of places is the garden. This comparison of the origin and the plants surrounding you, the garden, forest, jungle, I find it fascinating. And in that sense spiritual, potent, referencing God, religion, beauty and all these big powerful concepts, referencing ontology and how being is constituted.